Elaboration of Rosé

Did you know ?

A rosé wine is not a blend of red and white wine! It is wine made specially, with close attention given at every moment in its development, to the colour, aromas and taste that have made it such as success. Because of the precision and the attention to detail that it demands, of all the three colours, rosé wine is probably the most complicated to produce.

The colour of Rosé

Only the skins of black grapes contain colour pigments; the pulp, which gives the juice, is colourless. As a result, the colour of a rosé wine will depend on how long the skins and the juice are in contact, and at what temperature. This is known as the maceration process. It is also during this sensitive stage that the flavours of rosé wines are extracted. The vinification method also plays an important role: rosés that are directly pressed tend to be lighter in colour with low intensity, as opposed to rosés elaborated by means of skin maceration which will be of a more sustained colour. Lastly, the choice of varietals and the terroir also affect the colour and personality of a rosé wine.

Elaboration of Rosé : a delicate technique

In Provence, there are two main techniques used at this stage: skin maceration or direct press.

The choice of either technique is guided by several factors: the condition and ripeness of the harvest, the vinified varietals and their sensory potential, the choice of their proportions during blending and the desired sensory profile.

In both cases, making a rosé demands much more attention to detail in order to obtain an attractive colour and tastes that are both delicate and expressive.

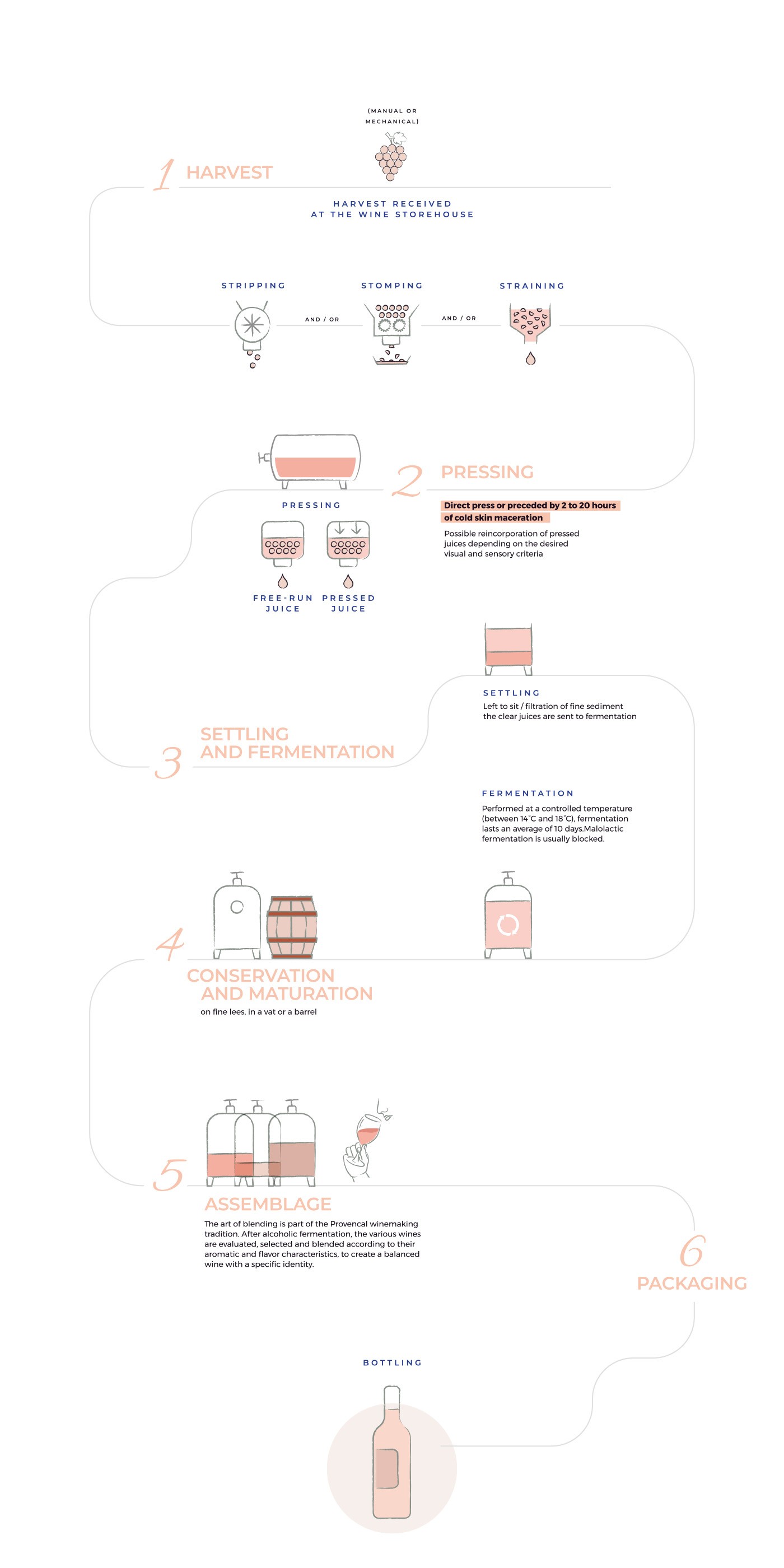

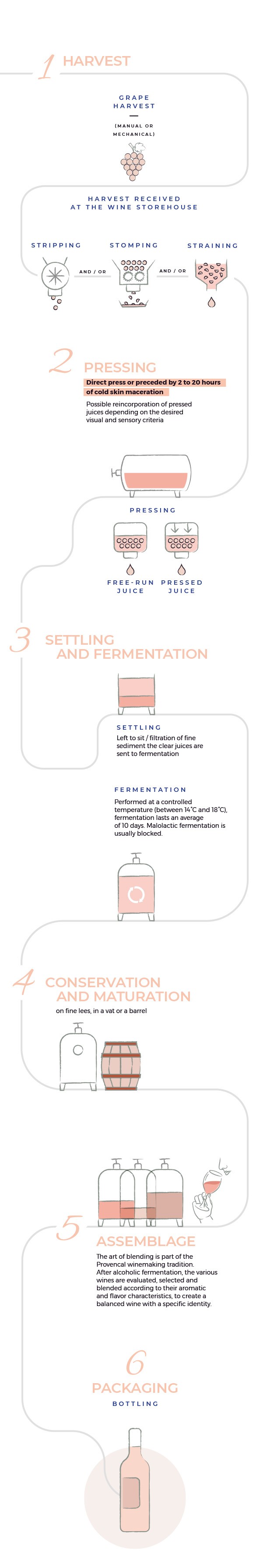

Provence : Rosé winemaking diagram

Skin maceration

Harvest

The grape harvest arrives at the cellar. Rosé is usually made from black-skinned grapes, although a small amount of white grapes can provide additional flavour and roundness.

Stripping

The grape berries are separated from the stalk (stem or woody part of the bunch).

Stomping

The berries are stomped. They burst and release the grapes’ pulp, skin, seeds and juice. This mixture is called the must.

Maceration

The must macerates in a tank for 2 to 20 hours at a controlled temperature of 16°C to 20°C. The pigments and flavours in the grape skins mix with the juice and begin to colour it. The juice takes on its lovely rosy hue.

Pressing

Once the juice reaches the colour that the winemaker wants, the must is pressed to separate the solid part (skins and seeds) from the liquid (juice).

Fermentation The juice ferments at a low temperature (18°C to 20°C) to preserve the taste as much as possible. Fermentation takes an average of one week.

NB: Why is it called “cold skin maceration”? Because the low temperature delays the onset of fermentation. So there is no alcohol in the juice at the beginning of this process.

Direct press

This technique involves pressing the bunches directly (either whole or stripped), without macerating them first. In this case, they are pressed very slowly, giving the skins time to leach a light, delicately rosy colour into the juice. The liquid is then immediately put into fermentation.

Rosé wines that undergo direct press tend to be lighter in colour than rosés produced by skin maceration.

It should be noted that, in other regions, a third technique may also be used: saignée. That method consists of racking about 5% to 15% of the juice, after a few hours in the tank. The removed portion is then used to make rosé. The remainder is vinified as red wine.